What is Sacred Harp? |

|

| Historical

background

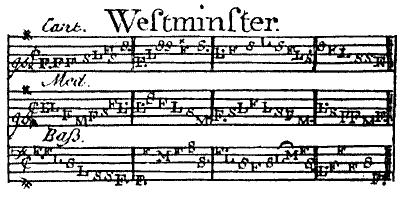

Music in the rural parish churches and chapels of England in the eighteenth century was lively, vibrant and robust. The congregations sang the tunes of artisan composers, who were relatively untrained in the rules of harmony and counterpoint, and set to the texts of Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley and John Newton, which offered a way of looking at life and death that challenges the standards by which we live our lives today. Taught in a form of solfege based on that of Guido D’Arezzo, this historic music form all but died out in England by the middle of the nineteenth century, but in an earlier migration to New England it took root, grew and eventually evolved in the Southern States into a singing tradition which continues beyond the twentieth century.

Shaped notation

D’Arezzo devised the

hexachord

and used the syllables UT, RE, MI, FA SOL and LA as a teaching aid

to 11th-century choir boys in Italy.

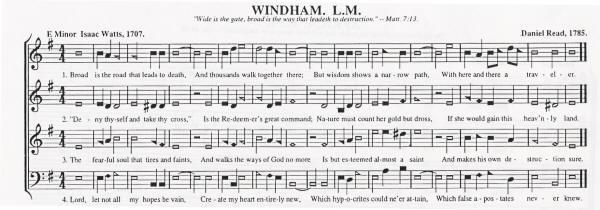

The system quickly became popular throughout western Europe, but in England the first two syllables were soon dropped, leaving a repetition of the syllables FA, SOL and LA, ending with MI to form the major scale. This teaching aid went over to New England in the early 18th century and was printed as part of the tuition instructions at the front of most psalm tune books, sometimes substituting the notes on the staves with the first letter of each syllable. In 1786, a man called John Connelly, living in Philadelphia, devised four specially shaped note heads to correspond with the solfege names, with FA having a triangular notehead, SOL a circle, LA a square, and MI a diamond.

He sold the idea to William Smith and William Little, who used it for the first time in a compilation of psalm and hymn tunes called The Easy Instructor, which they brought out in 1800/1. In 19th-century England, the development of Curwen’s Tonic Solfa, with DOH, RAY and ME as the first three notes of the scale and demonstrated so popularly by Julie Andrews in ‘The Sound of Music’, brings the history of this 1,000 year-old system up to date.

The Sacred Harp, 1844

In 19th-century America, some of the old psalm tunes managed to survive, by migrating down the Appalachians in collections of music which included new works by composers from the Southern States, set to Evangelical texts in preference to Isaac Watts. The last of these collections, The Sacred Harp, first published in 1844 and the only book of its kind to remain in continuous publication today, uses the same shaped notation first seen in The Easy Instructor.

Sacred Harp singing in the 20th and 21st centuries

Over the last 25 years, both in New England and in the UK, there has been a growing interest in learning more about this little known part of our shared musical history. Oxford Sacred Harp Singers offer an opportunity to experience the exuberance of over 200 years of English and American psalmody, which is still to be found within The Sacred Harp. This compilation of church music, both British and American, and using shaped note heads, was first published in Georgia in 1844. As the last collection of music produced in this form, it has survived and thrived in the Southern States of the USA to this day. Undergoing several revisions over the previous 150 years, the 1991 edition of The Sacred Harp brought together some of the gems by 18th-century New England composers like William Billings and 20th-century born Hugh McGraw, Ted Mercer and Bruce Randall.

Oxford Sacred Harp singers

Our aim is to give an insight into the history of psalmody both in 18th-century England and in the New World, and a taste of exciting and vibrant music, which is still very much a living tradition today. We recognise that different methods of teaching work for different people, so we offer schooling in Sacred Harp music both aurally, and from written notation. Each weekly session will commence with a singing school for beginners. Whether participants read ordinary music notation or learn by ear, singers of all ability are welcome.

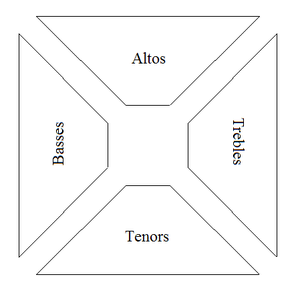

This form of music is not practised or sung in a regular ‘choral’ setting. Singers are seated in a square, with blocks of voices facing inwards, and the leader in the centre. Experienced singers will take it in turn to choose a piece from The Sacred Harp and lead it, singing the solfege or syllables attached to the noteheads before the printed text. There is no substitute for the sound in the middle of the hollow square and those new to the music are encouraged to join a leader to have the full surround-sound experience.

What needs to be established early on is what voice part suits an individual singer. Men with low voices would probably gravitate to the bass section, and women with low voices the alto line. Women with higher voices would probably be comfortable on the soprano line, or the treble line as it is called in this form of music. The tune is carried by the tenor section – as was the tradition in the 18th century – and can be sung up or down the octave by both women and men. Some men with higher voices also double the treble line an octave down, which can make for an exceedingly rich sound.

For newcomers to this music there is a lot of information to be processed and questions to be asked. It is impossible always to work at the pace of the slowest, but we do recognise that the comfort of the individual is important, and we offer the opportunity for participants to feed back to the group anything they felt needed more explanation or time, as well as aspects of the singing they particularly enjoyed. Although the texts we sing are of a religious nature, we welcome those of all faiths and none. Sacred Harp singing is open to all and for all to bring to it and to take from it what they will.

Sheila Macadam 30 Eynsham Road Botley, Oxford OX2 9BP Tel: 01865 865773

E-mail:

sheila@oxfordsacredharp.org or |

Further reading! Music theory on line: staffs, clefs & pitch notation, by Dr Brian Blood.

Music Takes a Sacred Shape; article in the Church Times by Simon Jones. References:

|