I can't remember, either, the last time I had an experience in church that was as affecting as this would turn out to be. No one preached. No one even prayed. But someone definitely stirred the waters.

St George's, Bloomsbury, has a concert list that stretches from rock to Baroque, but there is no concert tonight. People stream in, and sit in four sections around a central square. A softly spoken American man enters, offers a welcome, and announces: "This is not a performance. This is not a rehearsal. This is the thing."

ANDREW FIRTH

Note taken: Aldo Ceresa leads the session

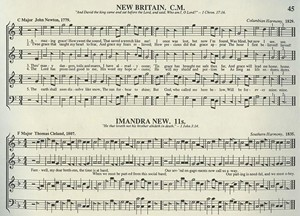

The "thing" is Sacred Harp shape-note singing, America's earliest independent music of European de-scent. A distinctive combination of traditional song and hymnody, it first became popular in singing schools, whose purpose was the correct understanding of religious music - religious music as it was understood in the country parishes of 18th-century England.

"Shape notes", written down, resemble the standard round notes that any musician will recognise. But the head of each note has one of four shapes to indicate its interval from the key note. The four-shape system (fa = triangle; sol = oval; la = square; mi = diamond) enabled - still enables, as I was to discover - musically untrained singers to sight-read music.

Over time, this a cappella style fused with local southern music, deviating from European tastes with a stark but robust infusion from the folk tradition. "White spirituals" some called them (somewhat curiously, since the form has a black tradition, too).

Note taken: shape notes look different from conventional notation

THE number of hymn-books that adopted the system demonstrate its value. The Kentucky Harmony was the first, in 1816, followed by the 1820 book used by Abraham Lincoln, The Missouri Harmony. Later titles reveal the geographical popularity of the form, but by the time of Southern Harmony (1835) and The Sacred Harp (1844), the non-classical deviation was too much for the metropolitan churches in the north, which reintroduced a sweeter, stricter European style.

Shape notes were still used, but in a more refined seven-figured system. When the Civil War broke out, the Sacred Harp - a sanctified term in the south for the human voice - was sung almost exclusively below the Mason-Dixon line. It has been in continuous use there ever since - longer than any other hymn-book, anywhere.

I first heard songs from its pages on Harry Smith's album Anthology of American Folk Music, a collection that launched the folk revival and inspired Bob Dylan and others in the 1950s. It carried two rousing numbers by the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, made in 1928: "Rocky Road" and "Present Joys".

The haunting sound was, I discovered, taken from a rare field recording, since Sacred Harp singers did not perform for an audience. Singings are community experiences, shared and participatory. I live an ocean away from the Appalachian mountains; so it was not something that I was going to be able to pursue, however enchanting the sound.

In the new digital world, however, community is not restricted by geography. Members of the folk tradition in the United States found that, because of the simplicity of the notation, and with enough visits to the south, they could teach the method not just to other musicians, but to anyone who was interested in singing.

ANDREW FIRTH

Sol fa, so good: Simon Jones sings his first notes

A CURIO at first, the form began to spread once more, reaching its cousin tradition in the UK. (The singer Cerys Matthews was the presenter of a Radio 4 programme about the genre on Monday, which is still available on BBC iPlayer.) There are now a thriving British network, and a London Sacred Harp group that meets three times a month to sing.

One of these sessions is aimed specifically at beginners. Its website announces: "Although this is sacred music, we welcome all and practice (and expect) tolerance and respect for all singers, irrespective of belief or lack thereof, and we never ask anyone about their religion or politics. Indeed: this is one of the more diverse and welcoming singing groups you will ever come across." I'm there in droves.

I don't know where to sit, though. I tentatively perch at the back of one of four sections of pews that face a hollow square. Despite the tip-off on the website, I assume that the people streaming into the church - young hipsters, old hippies, and everything in between - must be on the way through to some other event downstairs. But as they begin to take seats, they offer nods of welcome, and someone suggests that I sit in the section that faces the altar. It is not like being welcomed on a Sunday morning - all smiles and no laughing. It's like being made welcome.

ANDREW FIRTH

Sol fa, so good: Michael Walker leads off

My section is for tenors, which I'm told is the best place for a beginner. To the left of the square sit the basses. Opposite me are the altos, and, to my right, the trebles. Someone passes me a fat, oblong book, and there it is in gold type, The Sacred Harp. As I begin to leaf, bewildered, through a section entitled "Rudiments of music", a man enters the square, having read my - and perhaps every beginner's - thoughts. His name is Aldo Ceresa, and he is visiting from a Sacred Harp group in New York. He and another American, Michael Walker, who is based in London, will be our teachers for the evening.

"BEWILDERMENT is normal," Aldo says. "This is a form devised for people who attended church every Sunday. It will take a while. It will probably take you six months. But it won't take you as long as a classical-music education. And you will be able to join in tonight."

He then begins to talk about the key community component of Sacred Harp in a way that exactly mirrors the music. It turns out that it will take us a while. But we are friendly. And, tonight, we will make a start at the pub.

The learning is learning, and better done than talked about, but some important principles emerge. Everything is done in full voice, and singing fortissimo (extra loud) on the beat matters more than hitting the right note.

If we were interested in perfect execution, we would be singing sweetly in the north. But rhythm matters. Whoever is leading the class - and it changes, song by song - needs to beat it out in the air, as do the front rows of each section. Without rhythm, there is no drive or pulse. Without drive or pulse, there is no shape note.

For most of this, I am still bewildered, as predicted. I mix up my square "las" and my triangle "fas" as we go through some scales, but this is expected. "Just sing 'fla', Aldo says. "I still do, sometimes." This matters, because each song begins with its lines sung out "fa", "sol", "la", "mi", rather than with its actual words. It helps everyone to get the tune.

ANDREW FIRTH

Sol fa, so good: the group gathers in a square

Eventually, we ready ourselves for a song. Aldo picks one I know as "Amazing Grace", rendered in Sacred Harp as "45t New Britain". In the book, each hymn is prefixed with a Bible verse; "45t" has 1 Chronicles 17.16: "And David the king came and sat before the Lord, and said, Who am I, O Lord?" By the time we've finished, I feel just as humbled.

THE sound is like nothing I have ever heard before - and I grew up in a Welsh chapel. It's as deep as funeral music, but feels like a resurrection. When Michael invites newcomers into the hollow square to get the full surround-sound experience, my insides crack like a flagstone.

This time, it's "354t Lebanon": "Oh turn us, turn us, mighty Lord, by thy resistless grace", but although the moment feels unutterably, overwhelmingly holy, I don't know that the words have much to do with it. I feel like Naaman risen from the Jordan. Like Elijah as the fire falls from the sky. I cannot, ever, not do this.

In the pub afterwards - and we all go - I ask Aldo about the difference a faith makes to the experience.

"We have people of all faiths and none, as you'll find out," he says. "But what's interesting is that the agnostics say that the music cannot be denuded of its religion. Some of these are folk tunes, and we could find non-religious words, but its power is its spirituality."

Michael agrees. "I play organ in a church, and I'm a believer, but I'm fascinated by the effect this music has on people who don't believe. What is it that means, after singing, that these people want to form such a close community? If we talked religion here, I'd say it was something like mission."

Eimear, a regular whose deep bass belies his lanky frame, sees it differently. "The form is profound; but this music was helped by people who weren't religious. It was dying out in the south, and then the folk tradition got hold of it. Then the punks, who wanted something with the same intensity," he says.

This strikes a distorted chord with me: having bashed about in several ropey punk bands, I can see exactly why my New York counterparts were drawn to this raucous sound that their folk friends had fetched up from the south.

"Community is something we all want, and this is how we allow ourselves to have it," Eimear says. "Singing full voice, facing each other, is a way of being vulnerable with each other."

THERE is something more than religion in the words, too. Sarah regularly drives up from Sussex for the session, and tomorrow will go to Buckinghamshire for an all-day singing. You could call her a devotee.

"Look at how much death is in these songs," she says. "The tradition has a big focus on mourning, and one of the things that's happening is that we become a place that allows ourselves these thoughts. Death is excluded from most social conversation. We fear it and flee it. In these hymns, we look it in the eye."

I ask another shy newcomer what she made of it, and how comfortable she was with the religious texts. "Something happened that made me feel like I was part of something bigger," she replies. "I don't think it matters whether you call that 'God', or 'community', or the 'collective unconscious'. When all those hands were going up to the beat, I kept having to tell myself: 'Not a cult, not a cult, not a cult,' because it looks so weird, but what I do know is that this is me, now, for ever."

A similar expression is found in the US, where traditional Sacred Harp churches in the south find themselves visited by northern newcomers in search of the authentic shape-note experience. As interest in the form grew, the film director Matt Hinton made a film, Awake My Soul, in an attempt to capture the experience. He later called it a rare example of "blue state/red state harmony".

Given Sacred Harp's subject matter - pilgrims, graves, sin, and the blood of Christ - its survival outside the Church is pretty startling. Even inside it, we tend to veer away from such language. Equally, its musical style could be said to be obsolete by two centuries, while its notation looks like unevolved hieroglyphics.

And yet it is also democratic, in a fresh way; non-performative, with no identifiable location of power - as counter-cultural in its modernity as its tradition.

Could it be a model? "Although this is sacred," I remember the website saying, "we welcome all and practice (and expect) tolerance and respect for all . . . irrespective of belief or lack thereof. " The result: "One of the more diverse and welcoming groups you will ever come across." Amen.